Trends in Gifted Education: Fair Identification Best Practices

Gifted education is constantly evolving to better meet the needs of gifted learners. In recent years, gifted identification practices have become fairer and more comprehensive¹. At its core, fairness in gifted education ensures all students have equal opportunities to demonstrate their ability without being unduly influenced by their demographic background or previous opportunity to learn. This fairness lens influences all aspects of gifted education—from policies to testing, identification, programming, and in-classroom applications and practice—that meet the needs of gifted students. Through more thorough identification methods, a personalized and fair approach to gifted education can be achieved for all students receiving the support and opportunities necessary to flourish.

Some key trends in gifted identification include:

- Selecting fair assessments

- Universal testing

- Use of multiple assessment criteria

- Alternative identification pathways

- Different domains of giftedness

1. Selecting Fair Assessments

There is a growing momentum towards selecting fair assessments for the identification of gifted students. Implementing this trend into practice involves selecting assessments that are developed with features that can fairly assess demographic groups that have historically been overlooked, such as students from diverse racial, ethnic, linguistic, or socioeconomic backgrounds², ³.

For example, MHS’ Naglieri General Ability Tests™ were developed by Jack A. Naglieri, Ph.D., Dina Brulles, Ph.D., and Kimberly Lansdowne, Ph.D., to address the need for fair assessment through the incorporation of features that could lead to more fair identification results. The Naglieri General Ability Tests feature minimal language demands through animated video instructions; the elimination of written and spoken language in all test items; reduction of academic content in test items to minimize the impact of previous knowledge; and expert cultural review of items to minimize cultural influence in the item imagery. A study by Selvamenan et al. (2024) investigated the relationship between ability test scores and demographic groups when fair test design features are implemented⁴. A large sample of census-matched students completed each of the Naglieri General Ability Tests (Naglieri–Verbal, N = 2,482; Naglieri–Quantitative, N = 2,369; and Naglieri–Nonverbal, N = 2,383), with results showing minimal differences in scores between demographic groups for race, ethnicity, gender, and parental education level.

For tests that inherently require language as part of the measure, a fair-access approach involves ensuring the test is available in multiple languages and minimizes the use of culture-specific content, which can affect a test-taker’s ability to answer appropriately. MHS’ Gifted Rating Scales™ Second Edition (GRS™ 2) developed by Steven I. Pfeiffer, Ph.D. and Tania Jarosewich, Ph.D. includes a parent measure available in both English and Spanish. Items within the GRS 2 were also reviewed and revised to improve the following: readability, content clarity, and an elimination of culture-specific language or idioms.

By focusing on the development and use of fair tests, educators can better identify gifted students from overlooked groups and ensure that all students have an equal opportunity to be recognized for their unique abilities. This trend is crucial for supporting a fairer gifted education system.

2. Universal Testing

Universal testing is becoming an increasingly popular approach to identifying gifted students. In the past, gifted identification has relied largely on teacher referrals or parent nominations, which can be susceptible to subjective judgment. As a result, many students from particular groups, such as socio-economically disadvantaged students, or Multilingual Learners, have been overlooked for consideration into gifted programs⁵.

Universal testing ensures that every student is given an equal opportunity to demonstrate their abilities. Research shows that universal testing can increase the likelihood of being identified as gifted by 174% for disadvantaged students who may have otherwise gone unnoticed when using alternative approaches⁵. This approach involves administering a standardized assessment to all students within a certain grade, school, or district, rather than assessing only a select few candidates. The results from this stage are then used to identify potentially gifted students for further evaluation.

Universal testing should incorporate local norms to promote fairness when the demographic makeup of the school or district does not match the national norm, ensuring students are assessed relative to peers within their own community, which better reflects local demographics. Universal testing can be effectively implemented through various methods, such as ability tests, achievement tests, and parent or teacher ratings.

3. Use of Multiple Assessment Criteria

The National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC) states that best practices in gifted identification involve collecting student data from both objective tests, such as performance measures completed by the student, and subjective measures, like parent- or teacher-completed rating scales⁶. The use of multiple assessment criteria for the purpose of gifted identification provides students with multiple opportunities to demonstrate their ability across different domains and contexts. Key considerations when implementing multiple measures include the type of measures and the variety of test content within a measure.

For instance, the Naglieri General Ability Tests is a performance-based measure, allowing students to demonstrate their general intellectual ability by reasoning through tasks using verbal, non-verbal, and quantitative content. On the other hand, the GRS 2 allows teachers or parents to rate a student across various observed domains of giftedness. These two measures can serve as complementary tools by providing a comprehensive view of the student’s ability and potential across multiple contexts and datapoints.

Using multiple measures, as a best practice, contributes to a more fair and comprehensive assessment process in gifted identification⁶. A student’s demonstrated ability can be incorporated with other types of information, such as motivation and creativity, across different contexts to ensure more opportunities to capture students’ strengths. Evidence from multiple datapoints also help align identification methods with programming goals by recognizing students’ strengths in specific areas and highlighting students whose results may indicate their potential to perform at high levels.

4. Alternative Identification Pathways

Alternative identification pathways involve using multiple types of assessment to identify students for gifted programs while also accounting for the weighting and interpretation of results across measures. Factors such as the selection of cutoff scores, the type of norms used, and how scores across different assessments are combined can all influence who is identified in the student population. It is crucial to ensure that the pathways to identification do not lead to unfair “gating” practices that may exclude certain students. For instance, if students are only tested using a nomination method, rather than through universal testing — and the chosen screener is observation-based only — positions students with barriers and missed opportunities to demonstrate their ability and potential.

Additionally, Peters et al. recommend using alternative assessment methods, such as “and” and “or” rules when determining cutoff scores across multiple measures⁷. An “and” rule would require a student to score highly on both measures when multiple assessments are administered. Alternatively, an “or” rule will allow a student to be considered for gifted programming if they meet the cutoff score on at least one of the tests administered. Fortunately, assessments like the Naglieri General Ability Tests, which include three distinct measures of general ability using verbal, nonverbal and quantitative content, are well suited to an “or” rule approach where students who demonstrate a strength on any one test may be considered for identification.

5. Different Domains of Giftedness

That said, there has been an increasing awareness that giftedness encompasses far more than just traditional academic skills. Historically, giftedness has been viewed through a narrow lens that primarily focused on academic abilities or demonstrated achievement in specific subjects like mathematics or language arts. Students exhibiting exceptional abilities in other domains are, as a result, unrecognized. This shift in the conceptualization of giftedness has broadened the definition to include multiple domains of giftedness, such as artistic talent, creativity, resilience, social competency, and leadership. Emphasizing that giftedness is multifaceted and can manifest in a variety of ways beyond academic domains or achievements allows educators to better identify and nurture these potential talents in a diverse group of students.

Fair identification of gifted students requires a broad perspective on what it means to be gifted. A student who excels in artistic ability, but not academic ability, still has significant potential to shine. By expanding the scope of what it means to be gifted, educators can more effectively and fairly ensure that all students — regardless of their background — have the opportunity to be recognized for their unique strengths. Recognizing different domains of giftedness in turn benefits students by acknowledging their specific talents so that they can receive more tailored opportunities for growth and differentiated instruction.

For example, when using the GRS 2, a student who is identified as likely gifted on the Artistic Ability scale might thrive in a specialized art program, whereas a student identified as likely gifted on the Leadership scale may benefit from a collaborative or project-based learning opportunity. Recognizing multiple domains of giftedness helps to foster broader opportunities for all students to be acknowledged for their strengths.

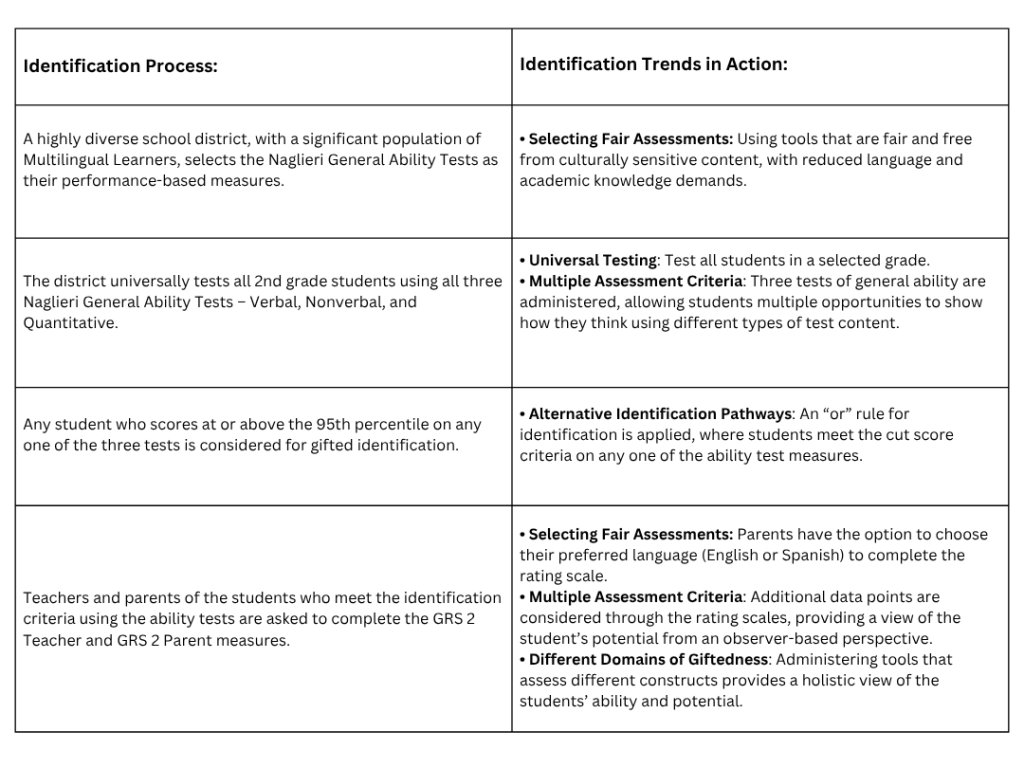

Consider the following case study, which illustrates how the combination of these identification trends can be applied for a fairer and best-practice approach.

When fair test selection, universal testing, multiple assessment criteria, alternative identification pathways, and recognition of diverse domains of giftedness are implemented together, they create a system grounded in fairness that effectively identifies a diverse group of gifted students in need of additional learning resources. Beyond identification, these fair identification practices also enable educators to provide differentiated instruction and tailor their teaching methods to the unique needs of gifted students. These trends reflect a broader shift towards more personalized, fair, and holistic approaches to gifted education.

When fair test selection, universal testing, multiple assessment criteria, alternative identification pathways, and recognition of diverse domains of giftedness are implemented together, they create a system grounded in fairness that effectively identifies a diverse group of gifted students in need of additional learning resources. Beyond identification, these fair identification practices also enable educators to provide differentiated instruction and tailor their teaching methods to the unique needs of gifted students. These trends reflect a broader shift towards more personalized, fair, and holistic approaches to gifted education.

Curious to learn more about the Naglieri General Ability Tests™? Reach out to a member of our team today.

References

¹ Şakar, S., & Tan, S. (2025). Research topics and trends in gifted education: A structural topic model. Gifted Child Quarterly, 69(1), 68–84.

² Gentry, M., Gray, A., Whiting, G., Maeda, Y., & Pereira, N. (2019). Gifted education in the United States: Laws, access, equity and missingness across the country by locale, Title I school status, and race (Report cards, technical report, and website). Purdue University. Jack Kent Cooke Foundation.

³ Long, D. A., McCoach, D. B., Siegle, D., Callahan, C. M., & Gubbins, E. J. (2023). Inequality at the starting line: Underrepresentation in gifted identification and disparities in early achievement. AERA Open, 9.

⁴ Selvamenan, M., Paolozza, A., Solomon, J., & Naglieri, J. A. (2024). A pilot study of race, ethnic, gender, and parental education level differences on the Naglieri General Ability Tests: Verbal, Nonverbal, and Quantitative. Psychology in the Schools, 61(12), 4705–4731.

⁵ Card, D., & Giuliano, L. (2016). Universal screening increases the representation of low-income and minority students in gifted education. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(48), 13678-13683.

⁶ National Association for Gifted Children. (2019). Position statement: A definition of giftedness that guides best practice. Retrieved from https://www.nagc.org/sites /default/files/Position%20Statement/Definition%20of%20 Giftedness%20%282019%29.pdf

⁷ Peters, S. J., Gentry, M., Whiting, G. W., & McBee, M. T. (2019). Who gets served in gifted education? Demographic representation and a call for action. Gifted Child Quarterly, 63(4), 273–287.