Making assessments fair using the principles of universal design: The Pediatric Performance Validity Test Suite

What is the Pediatric Performance Validity Test Suite (PdPVTS)?

When a youth undergoes any kind of assessment of their cognitive skills or abilities (e.g., tests of intelligence, tests of achievement, or neuropsychological assessment), they are asked to demonstrate the upper limit of their performance. Such tests are commonly known as maximum performance tests. For that reason, these types of tests will only provide an accurate reflection of a youth’s actual skills or abilities if they apply their best effort. It is therefore essential that examiners, be they school psychologists, clinical psychologists, or clinical neuropsychologists, have a way to evaluate objectively whether an examinee has put forth their best effort and are engaged fully with the assessment process. When working with adults, neuropsychologists address the risk that examinees may be withholding effort by using performance validity tests. The Pediatric Performance Validity Test Suite (PdPVTS) comprises a series of youth-friendly tests that were designed specifically to determine whether children and adolescents aged 5 to 18 years are giving their best effort across a wide range of evaluative settings.

Why is fairness an essential component of the PdPVTS?

Ultimately, any time a youth’s cognitive ability is assessed, there is a lot at stake; the information gathered typically is used to inform life-changing decisions. If the evaluation is not accurate, a youth could be led down a path that is fundamentally wrong for them, given their true abilities. This potentiality means that stakes associated with tools like the PdPVTS are also very high, given that the PdPVTS is used to make judgments about the integrity of a youth’s evaluation. Because of the gravity of the decisions the PdPVTS informs, it is imperative that the PdPVTS is as fair as possible. In other words, the interpretation of the PdPVTS should remain the same for all the different groups of youths who might take it. To ensure that the PdPVTS would be fair to all groups, the PdPVTS was built on the principles of Universal Design.

Fairness by design: Building the PdPVTS on an equitable foundation

Historically, the issue of fairness in test development has largely been something of an afterthought. Fairness was often examined by looking for mean differences in test outcomes among nominally defined groups of test-takers, an endeavour that usually took place in the late stages of the test development process. This approach has also become the most universally rejected definition of bias in the psychometric literature (i.e., the mean differences approach). Universal Design represents a radically different approach. The concept of Universal Design originated in context of architecture where an emerging philosophy was that the built environment should be designed to be accessible to all people, regardless of their physical ability, rather than adapted after the fact. Today, these principles are applied across a wide range of disciplines, including test design. In the context of test design, Universal Design refers to the development of fundamentally fair and inclusive tests that take all possible test-takers into consideration at each stage of the development process. Critically, this includes the seminal stages of development, such as defining the construct that is being measured and creating the test items that are being used to measure it.

In keeping with Universal Design principles, the PdPVTS made fairness a central focus from the very outset of its six-year development process, starting with the items that were used on each constituent test. The PdPVTS comprises four visual tests (Find the Animal, Matching, Shape Learning, Silhouettes) and a verbal test (Story Questions, with different age-appropriate stimuli for ages 7-11 and ages 12-18). For each of the visual tests, a great deal of care and attention went into selecting images that would not be biased toward any given cultural group. Any images that might resonate with specific gender or racial/ethnic groups were minimized. This approach meant that images of clothing, flags, landmarks, symbols, or icons were avoided completely. For the verbal tests, the words that were used were also carefully selected to avoid these same potential sources of bias and to ensure they were developmentally appropriate for the target age range. During the item development process, item content was examined by cultural consultants and expert reviewers to help identify any items that might be interpreted differently as a function of gender, race/ethnicity, cultural background, socioeconomic status, or age and developmental level. Statistical analyses were then used to identified items that show differential item function (DIF) as a function of nominal groupings such as ethnicity and gender.

The PdPVTS was also designed with accessibility in clear focus from the very outset. Different modes of administration (i.e., visual tests vs. verbal tests) were used so that the PdPVTS would be able to accommodate different levels of physical and cognitive ability. For example, the verbal tests can be used to assess youth who cannot use a touchscreen to complete the visual tasks due to motor impairments or visual impairments, whereas the visual tasks can be used with youth who have hearing impairments or who may have issues with verbal comprehension (e.g., those with intellectual disabilities or those who are not native English speakers).

How does the PdPVTS demonstrates evidence of fairness in practice?

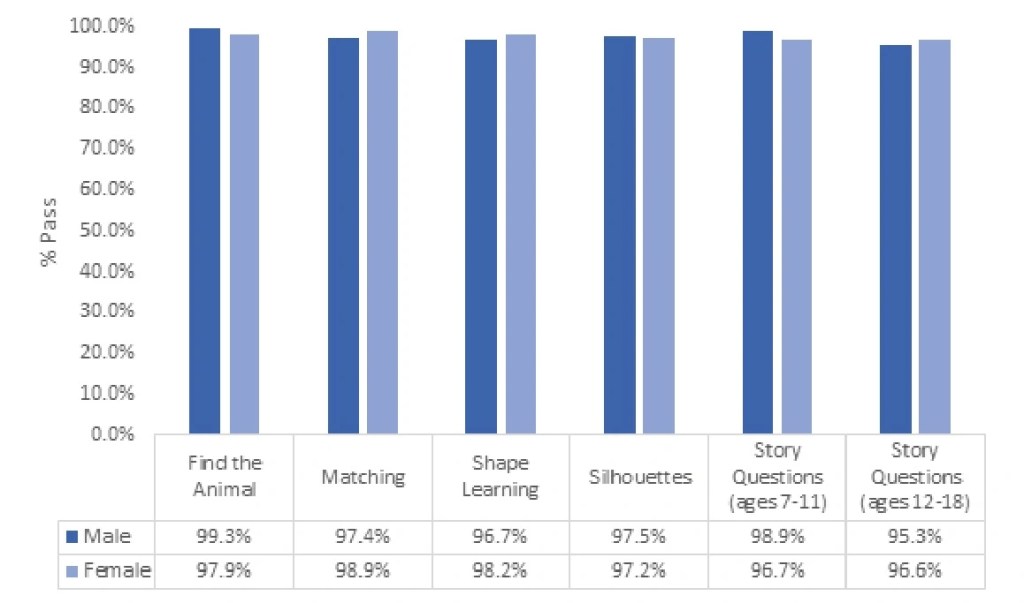

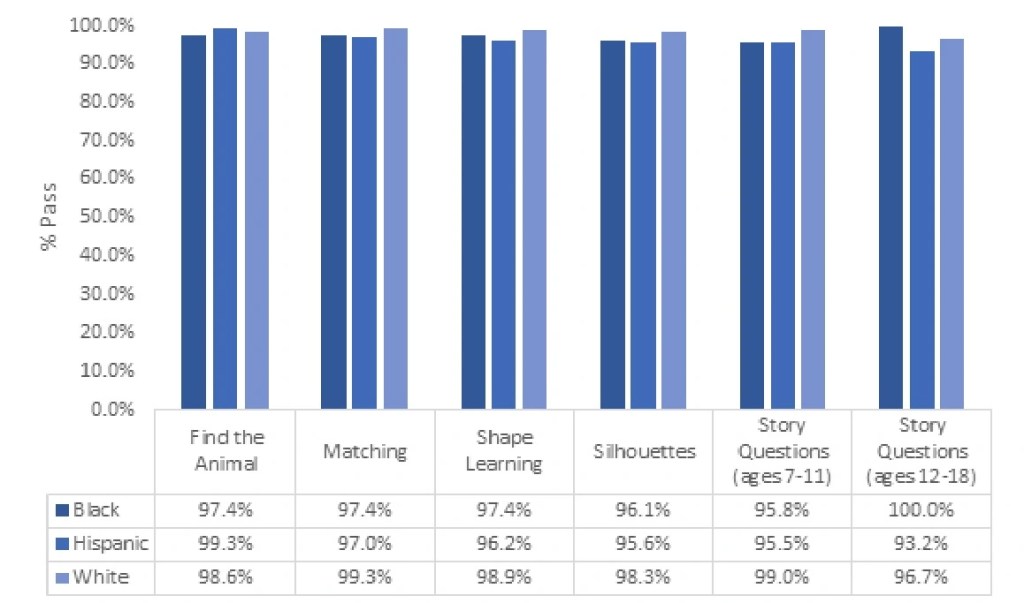

The main objective in applying Universal Design principles to the development of the PdPVTS was to ensure that the interpretation of the PdPVTS results would remain the same across different groups of test-takers. Ultimately, we observed strong evidence to demonstrate that the Universal Design approach was a resounding success. To illustrate, when comparing the results on each of the tests that comprise the PdPVTS between key demographic groups, there was no evidence of gender differences (see Figure 1) and no evidence of differences based on racial/ethnic group (see Figure 2). There were no statistically significant differences among groups and all effect sizes were negligible to small, indicating that youth identifying as male or female, as well as White, Hispanic, and Black youth all have similar probabilities of passing each PdPVTS test when optimal effort is given.

Figure 1. Pass rate by gender across PdPVTS tests

Figure 2. Pass rate by race/ethnicity across PdPVTS tests

Taken together, this evidence illustrates that incorporating Universal Design principles into the development of the PdPVTS and making fairness a central objective from the outset of the development process yielded a set of tests that are inclusive of different groups of test-takers. In practice, this finding means that psychologists can use the PdPVTS with full confidence that the results will provide an objective indication of whether an examinee’s performance is an accurate representation of their skills and abilities, regardless of the demographic characteristics of the youth being assessed. Therefore, psychologists can make more accurate decisions about a youth’s presentation, leading to more positive outcomes.

To learn more about the Pediatric Performance Validity Test Suite or to purchase, click here.