Build A Model For Gifted Services That Promotes Diversity And Inclusion

The interview below has been edited for length and clarity.

First, I’d like to get a little bit of background on the current landscape of gifted service models. Which delivery models are most prevalent among gifted programs in the United States today?

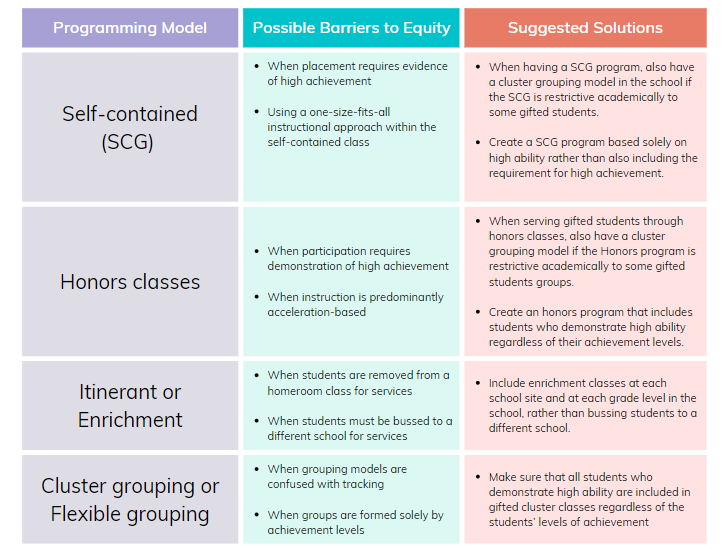

DINA: The four most popular models are: cluster grouping, enrichment classes, honors classes, and self-contained gifted classes. The table below contains more details on the possible barriers to equity within each of the models listed and suggested solutions. Cluster grouping is the most inclusive model. A main benefit for gifted students learning in a gifted cluster class is that they have like-minded peers with whom they can learn on a daily basis. When grouping students newly identified with the Naglieri General Ability Tests for example, it will become apparent that many of these students will also be grouped with peers from their cultural groups. This occurs when using building-level local norms because more culturally and linguistically diverse students will be identified overall. When grouped together for all their content areas, gifted students are more likely to challenge themselves, delve deeper into the content, and engage in critical and creative thinking. Here is a book I co-wrote on the model: The Cluster Grouping Handbook: A Schoolwide Model: How to Challenge Gifted Students and Improve Achievement for All (Free Spirit Professional™) Regardless of the method employed, gifted learners will benefit from these grouping practices by having opportunities to work at their levels of readiness and develop their interests.

What is your “check-list” so to speak that you’d like to see all providers following when building a service model from the ground up?

DINA: To achieve equity, schools must expand their views, procedures, and practices on the gifted identification process while providing tiered levels of services and instructional support based on students’ needs (Peters & Brulles, 2018). School personnel must be more responsive to students who have previously been disenfranchised by broadening and expanding gifted identification and services. This begins with inclusive practices for identifying giftedness. Once previously missing students are identified, the questions become:

- How do we serve our diverse gifted population?

- What do we do if these newly identified gifted students are not demonstrating the high levels of achievement that are needed for success in gifted programs?

- How can we determine if students are engaging in the gifted services being offered? What can we change when students do not actively engage?

- How can schools better structure their gifted programs in ways that are diverse, equitable, and inclusive?

Reflect on the following questions when considering the who, what, and how in building equitable programs:

- What actions can you take to increase diversity, equity, and inclusion in your program?

- What do you need to know to undertake these actions?

- What approach do you want to use?

- Who should be involved in the process?

To answer these questions, you will likely need to transition away from past practices and focus instead on changes that will transform your services. This involves examining what barriers exist and considering how to go about solving the problem.

Let’s take a step back and talk about identification a bit. Can you discuss your work with the Naglieri General Ability Tests and touch on how you identify students through more equitable means?

DINA: An increasing number of states in the US are now including a mandate to use local norms in a move to increase equity, open access, and develop more inclusive gifted services. Once students have been identified using local norms, districts must then make decisions for providing gifted services based on the school’s gifted student populations. Using the Naglieri General Ability Tests along with local norms is a proactive, strengths-based approach to gifted identification that does not rely on evidence of high achievement or on school-based knowledge.

Upon implementing new identification methods using local (e.g., building-level) norms, districts then need to differentiate the services they provide. Having different identification and programming criteria for each school in a district is being culturally responsive. In this way gifted services become organic and develop based on need. Expect that by using the Naglieri General Ability Tests and building-level local norms, you will need to prepare for different tiers of services.

We know that a cohesive relationship between the identification process and education programming for gifted and talented students must exist in order for any program to create positive impact and development. How can educators bridge this gap to make sure identification and programming match?

DINA: To rebuild gifted services in more equitable ways that promote diversity, stakeholders must consider and acknowledge their personal roles in perpetuating these unacceptable, yet entrenched practices. Rebuilding gifted services starts with awareness of how school policies can add to, and even set the stage for, disproportionate numbers of white, affluent students in gifted programming. Mindsets impact policies, so examining existing policies in light of changing mindsets should be a priority and a prerequisite when redesigning gifted programs.

A question that schools and districts throughout the United States wrestle with is, how can we achieve equity in ways that ensure all students can fully access academic, social, and emotional supports and appropriate services? Some schools and districts asking this question will find that they need to transition away from past practices and rethink their ideas about what is needed to transform their services. An agreed-upon premise to begin considering change might simply be that giftedness runs across all cultures, races, and ethnicities, as well as genders, socioeconomic statuses, and English language proficiency levels (NAGC, 2021). With that in mind, schools should expect and strive to identify and serve all gifted learners, and especially those who have been previously underserved. Once they reframe their vision in this way, schools can then ask the action-oriented question, what areas of our programming need to be reassessed?

Creating equity in gifted programs requires a systems approach. School administrators must thoroughly study and determine how existing structures perpetuate underrepresentation. Then identify what specific structures, such as resources, administrative initiatives, and district priorities could provide access, support, and resources to underserved students.

Proactively building gifted services that are designed to enfranchise underrepresented populations begins by building stakeholder support. Stakeholders include district administrators, principals, teachers, and parents. They need to be aware of gifted students’ specific needs, and the limitations and possible inequities for underserved populations that are inherent in existing structures. When advocating for stakeholder support, providing information to all groups associated with the school district is critical and becomes crucial for building sustainable services.

Educators should understand the learning and developmental differences of students who are gifted and talented. How best can educators assist students in the area of affective development?

KIM: One of the biggest myths about gifted students is that they will succeed on their own, that they don’t need specialized programs in school, but this is not the case. Gifted children deal with their surroundings in different ways than neuro typical children. Their thoughts, actions, and feelings are more intense. Additionally, in underrepresented populations in gifted programs, students harbor feelings of isolation and disenfranchisement.

Gifted students can be intense and may have a lot of self-doubt. Common among gifted students is the thought that maybe “I don’t belong” and “someone is going to find out I’m not really gifted.” This is especially true for underrepresented populations. I recently had a conversation with a highly gifted African American student at my school. He told me that he always feels like he is the only kid in the group that “looks like him.” Our hope (goal? desire?) with the Naglieri General Ability Tests is that more students who are smart but don’t fit the typical “look” of giftedness be recognized, acknowledged, and provided services to help them feel confident.

It’s also important to recognize that gifted students are advanced beyond grade level peers in some areas but some traits may lag behind age peers. This is defined as asynchronous development, also known as developing “out of sync.” Due to their asynchronous development, some gifted students feel lonely with age-peers in the general population. Most prefer to associate with bright, older children or adults. The lack of intellectual peers at the same age can be very isolating for children and can lead to depression, poor social behaviors, and underperformance in schoolwork (Hollingsworth, 1942). Even with the best intentions, teachers who have had little or no experience with gifted students are unfamiliar with how they learn, thus unintentionally exacerbating the students’ uneasiness at school.

Feelings of isolation and loneliness take on different forms depending on the student’s personal lives, the school setting, support system and culture. Dina tells the story of a student in her district who reported that she was so lonely she contemplated suicide while in her elementary years. Being the only Hispanic student in her gifted class she felt different and not accepted by the other gifted students. At the same time, her Hispanic friends treated her differently once she entered the gifted program. In her efforts to feel accepted in her gifted program she stopped speaking Spanish for an entire year. Clearly, she was confused about her identity and longed for acceptance and belonging.

The primary goal is to help gifted students find like-minded peers and friends. Using the Naglieri General Ability Tests, along with local norms, will provide a clear path for districts to build gifted programs that represent the demographics of their schools. This will build students’ confidence, sense of self and success in school.

Where would you like to see future progression or research focused on in the realm of Gifted and Talented service models?

KIM: Even though it is well documented that Black, Hispanic, Native American students have been denied access to gifted education for decades, injustice continues. In schools today, it is common to hear well-intentioned educators advocating for inclusion and equity, and many in society are calling for social justice and respect for diversity. Over several decades educators and researchers have identified this as a problem and much work has been done but WE CAN DO BETTER.

More research needs to be done with respect to:

- Students from historically marginalized groups who are intellectually capable (gifted) but perhaps not talented (knowledgeable), – how can they be more equitably evaluated?

- Culturally appropriate service models for gifted students of diverse and underrepresented populations.

- The work that needs to be done to correct longstanding inequities surrounding gifted identification and programming.

Learn more about MHS’ Gifted and Talented solutions.

About Dr. Dina Brulles and Dr. Kimberly Lansdowne

Dina Brulles, PhD, is the director of gifted education in Paradise Valley Unified School District in Arizona as well as the Gifted Program Coordinator at Arizona State University. Her work in these roles, along with her consulting and publications, emphasize and encourage inclusive identification practices and programming in gifted education. Dina serves on the NAGC Board of Directors as Governance Secretary and served two terms as School District Representative.

Dina received the 2019 and the 2020 NAGC Book of the Year Awards and their inaugural 2014 Gifted Coordinator Award. She co-authored the books: A Teacher’s Guide to Flexible Grouping and Collaborative Learning; Designing Gifted Education Programs: From Purpose to Implementation, Differentiated Lessons for All Learners; The Cluster Grouping Handbook; Teaching Gifted Kids in Today’s Classrooms; Helping All Gifted Children Learn; and the Naglieri Ability Test – Verbal (2021).

Kimberly Lansdowne, PhD, is the founding Executive Director of the Herberger Young Scholars Academy, a secondary school for highly gifted students at Arizona State University (ASU). She has a lengthy career in teaching and administration at universities, colleges, public and private schools. At ASU (2004-present), she develops and teaches undergraduate and graduate level education classes for Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. She typically teaches education courses on curriculum, instruction, testing, measurement and special needs.

She received the Arizona Association for Gifted and Talented Administrator of the Year award in 2014. She has served locally, nationally and internationally in organizations that advocate for gifted students: Arizona Association for Gifted and Talented (2000-2008), National Association for Gifted Children (2003-2010) Diversity and Equity Committee, and Center for Talented Youth, Ireland Advisory Board (2014-present).