Hiding in Plain Sight: Camouflaging in Adult Autism

Key takeaways:

- Many autistic adults work hard to “blend in,” using camouflaging strategies that can hide their true experiences, often at a personal cost.

- Because camouflaging can make autistic traits less visible, autism in adults is frequently missed or misunderstood by people who know them well.

- New research using the ASRS® Adult shows that camouflaging creates a measurable gap between what autistic adults feel internally and what others observe externally.

Autism in adulthood is often misunderstood, not because the signs aren’t there, but because many autistic adults work hard to hide them. Camouflaging can make daily interactions easier, yet it also creates gaps in how autism is recognized, assessed, and supported. As researchers learn more about this subtle yet powerful behavior, new tools are emerging to better understand how camouflaging shapes the autism experience.

What is camouflaging?

When discussing autism in adults, one term that increasingly comes up is camouflaging. But what does that really mean? Camouflaging refers to the ways someone with autism may try to hide or disguise their autistic symptoms in social situations. These behaviours can be intentional choices or subconscious decisions that a person is unaware of.1 These strategies can involve copying others’ behaviors, suppressing natural responses, or working hard to appear to fit in.2 For many autistic adults, camouflaging is a daily strategy used to meet social expectations, even though it can be tiring, and it may make their autism symptoms or related challenges harder for others to recognize.3

Why camouflaging complicates adult autism diagnosis

Camouflaging can make diagnosing autism in adults especially challenging. When an autistic person is highly skilled at masking their traits, whether it’s consciously or unconsciously, even those closest to them may overlook certain behaviors or underestimate the intensity of those symptoms. This gap in perception can contribute to missed diagnoses and delays in accessing the right support. As a result, researchers and clinicians are increasingly focused on finding reliable ways to measure camouflaging and understand how it shapes the presentation of autism in adulthood.

Measuring camouflaging using the ASRS® Adult

The Autism Spectrum Rating Scales™ Adult (ASRS® Adult)4 is an assessment tool designed for individuals 18 years and older. It includes 96 items that assess a broad range of characteristics and challenges related to autism. This rating scale provides two complementary perspectives:

- Individuals rate their own behaviors through a Self-Report form

- Someone who knows them well, such as a friend, family member, or partner, completes an Observer report

The ASRS Adult includes a Camouflaging scale that reflects the extent to which an individual reports making an effort to mask or downplay autistic traits.

To better understand this Camouflaging score, MHS collected data from 105 autistic adults who live in the U.S. or Canada. The participants had an average age of 31 years (SD = 12.3), and the sample was evenly split by gender (49% female, 49% male, 2% other gender). Each person completed the ASRS Adult Self-Report, and an observer who had known them for at least one year completed the ASRS Adult Observer form independently. Observers included relatives (46.6%), friends (35.0%), and spouses or romantic partners (18.4%).

What did we find?

We wanted to know whether the Camouflaging score changes the relationship between self-reported scores and observer scores on the ASRS Adult. Specifically, do scores on the Camouflaging scale affect how closely observers’ ratings match what individuals report about themselves? To explore this research question, we compared Self-Report and Observer scores for people with higher self-reported Camouflaging (T-score ≥ 60) and lower self-reported Camouflaging (T-score < 60) across four ASRS Adult scales: Total Score, Social/Communication, Unusual Behaviors, and DSM/ICD1. A consistent pattern emerged:

- When Camouflaging is low, observers tend to rate the individual’s ASD-related symptoms and behaviors as more frequent or severe than the individual rates themselves on self-report.

- When Camouflaging is high, observers tend to rate the individual’s ASD-related symptoms and behaviors as less frequent or severe than self-reports. That is, people who are masking their symptoms will report their own challenges and symptoms, but friends or family perceive the masked behaviors, leading to lower symptom endorsement.

These findings reflect the nature of camouflaging itself. When Camouflaging scores are low, individuals are not actively or as frequently masking their autistic traits. Observers can clearly see behaviors related to social/communication challenges or atypical and unusual behaviors, so their ratings reflect what they experience with the individual. At the same time, individuals may underreport their own behaviors because they do not notice them, do not view them as atypical, or do not consider them significant. This pattern leads to observer scores being higher than self-reported scores.

When Camouflaging scores are high, individuals are actively masking or compensating for autistic traits in social situations. As a result, Observers see fewer outward signs of difficulty because the behaviors are hidden or replaced with socially expected responses. However, the individual still experiences the underlying challenges internally, including the effort required to mask, leading to higher levels of stress and fatigue. This discrepancy in perception creates a gap where self-reported scores are higher than observer scores.

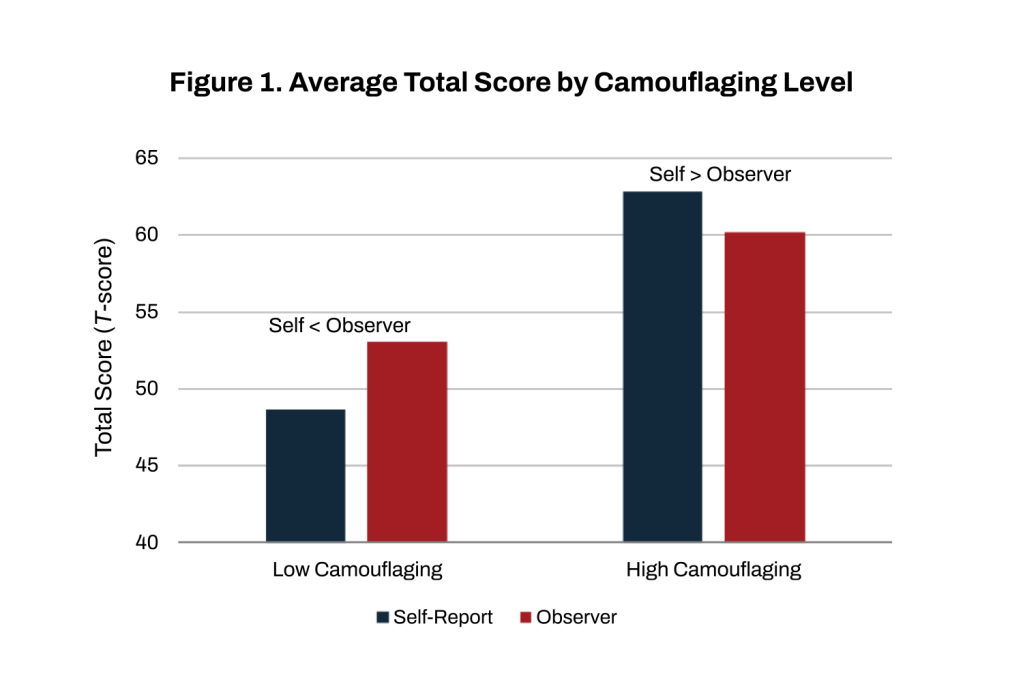

Below, Figure 1 illustrates this reversal using the ASRS Adult Total Score. The Total Score from Self-Report (autistic individuals) and Observer (their friends or family rating their behavior) are presented, divided by people who scored low (below 60) versus high (60 or higher) in self-reported Camouflaging. When Camouflaging scores are low, observer Total Score exceed self‑reported Total Score. When Camouflaging scores are high, the pattern reverses, as seen in Figure 1, and self‑reported Total Score exceed observer Total Score. This shift highlights how Camouflaging alters the alignment between internal experience and observable behavior.

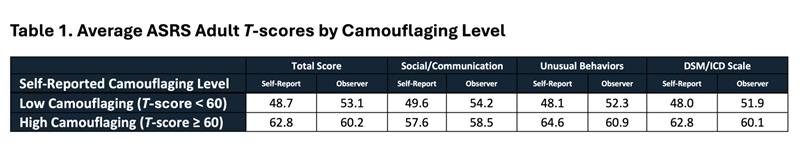

Table 1 presents average ASRS Adult T–scores on the Total Score, Social/Communication, Unusual Behaviors, and DSM/ICD scales by self–reported camouflaging level. These results demonstrate that the same pattern appears across other scales, though its magnitude varies. The largest differences occur in Unusual Behaviors and Total Score, moderate differences appear in DSM/ICD, and the smallest differences appear in Social/Communication.

What does this perspective gap mean for everyday life?

Camouflaging can help an autistic adult manage social situations, but it also makes traits of autism harder to see, even for people who know them well. As a result, people who know someone well may miss important details if that person is actively managing or modifying their behavior, especially in unfamiliar or formal settings. This gap in symptom perception is why gathering information from multiple perspectives is essential in autism assessment. Self-report captures the individual’s internal experience, while observer ratings provide an outside view. When both perspectives are considered together, and when camouflaging is measured and interpreted, clinicians and professionals are better equipped to form a complete understanding and provide meaningful support. Camouflaging can be adaptive and protective in some ways, but it can also create challenges with diagnosis and treatment monitoring, and it is an important aspect to consider in comprehensive evaluations.

Want to learn more? Visit the ASRS Adult storefront.

References

1 Lawson, W. B. (2020). Adaptive morphing and coping with social threat in autism: An autistic perspective. Journal of Intellectual Disability-Diagnosis and Treatment, 8(3), 519-526. https://researchers.mq.edu.au/files/164977020/Publisher_version.pdf

2 Bargiela, S., Steward, R., & Mandy, W. (2016). The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: An investigation of the female autism phenotype. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(10), 3281–3294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8

3 Tubío-Fungueiriño, M., Cruz, S., Sampaio, A., Carracedo, A., & Fernández-Prieto, M. (2021). Social camouflaging in females with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 2190–2199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04695-x

4 Goldstein, S., & Naglieri, J. A. (2025). Autism Spectrum Rating Scales Adult (ASRS Adult). Multi-Health Systems, Inc.

5 American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

6 World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/