Five Recommendations for Minimizing Bias in Risk Assessments

The use of pre-trial risk assessment tools around the world is widespread. In fact, risk/needs assessments are mandatory for sentencing in the adult system within 20 U.S. states. Since the use of these tools is so common, questioning the potential of their impact in creating racial disparity within the justice system is a daunting prospect. However, we know that the presence of bias is perhaps the most significant risk to the quality and efficacy of even the most carefully designed and executed risk assessments.

What do we mean when we’re talking about bias?

In this context, bias is a preconceived preference or inclination that can affect the impartiality of evaluations or decisions. The insidious danger of bias lies in the fact that it can take many forms and is not always readily apparent. Bias can result in risks being overlooked, inappropriately assessed, or prematurely dismissed.

In a recent webinar for MHS Public Safety, Dr. Gina Vincent, Associate Professor and Director of Translational Law & Psychiatry Research in Systems for Psychosocial Advances Research Center in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, outlined the background, history, and recent conversation of racial bias within risk assessment tools. Her analyses uncovered a complicated story.

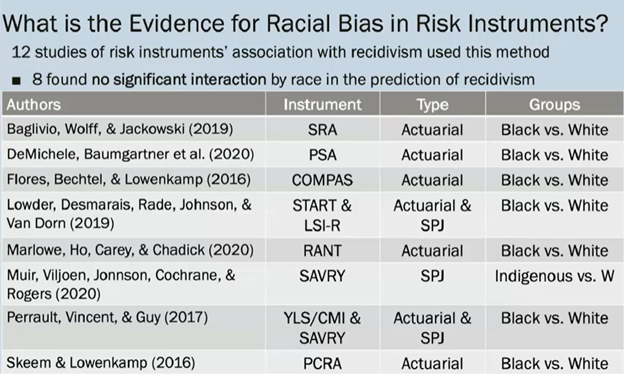

In the table above, Dr. Vincent outlines recent research she has undertaken reviewing evidence within studies focused on racial bias in risk assessments. Of the twelve studies reviewed, eight found no significant interaction of race in predicting recidivism. However, five tools studied indicated bias in several ways, including favoring certain groups (i.e., risk was rated lower than the actual rate of recidivism) and over predicting certain groups (i.e., risk was rated higher than the actual recidivism rate.) In summary, to date, the studies on risk assessment instruments have shown us racial bias in risk assessments has more to do with the tool itself than with risk assessments in general.

Ultimately, risk assessments and their methodology differ significantly. We can conclude that risk assessment instruments are not all created equal; however, empirically and appropriately validated risk assessments, when used properly, minimize disparities, and allow for structured discretion.

What can we do to prevent bias in our risk assessment?

In Dr. Vincent’s webinar, the following recommendations were outlined:

- Only use instruments that have been appropriately validated by race and do not rely solely on official records for its risk factors.

Ensure the assessment you’re using, especially pre-trial risk tools, is based on scientific standards and rooted in research on informed risk factors and psychometrics and not an author’s value-based judgments. - Never make decisions based solely on score-based risk classifications of risk.

These tools are meant to guide decision-makers in their process. From a scientific and measurement perspective, it’s not appropriate to make a decision solely based on a score. Every instrument has a band of error around its scores (standard error of measurement). Evidence-based practices rooted in the risk needs responsivity model recommend not dictating a decision for a high-risk individual solely on a score. An individual identified as high risk should not automatically be recommended for incarceration. This person may need more attention, and this further attention might be comprised of a higher level of interaction with supportive services. Take into account the different risk factors of the individual you are considering like their offense history, official records, environments etc. - Allow time to complete instruments containing dynamic risk factors when facing decisions where incarceration is a distinct possibility.

Dynamic risk factors give us more information about what a better management plan might be for an individual that may include options outside of incarceration. - Professionals need to delve deeper to recognize power imbalances in the field and implicit biases when weighing the relevance of specific risk factors to members from specific groups.

For other practical actions you can take to mitigate bias during the assessment process, take a look at this article from The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center: Three Things You Can Do to Prevent Bias in Risk Assessment. The CSG is U.S. based national, nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that combines the power of a membership association, representing state officials in all three branches of government, with policy and research expertise to develop strategies that increase public safety and strengthen communities. - Agencies should keep track of outcomes by race, ethnicity, gender, and other characteristics.

Ensure that your risk assessment instruments do not create disparate impact for specific groups. By keeping track of this information, the data collected will help you understand if individuals are being treated fairly.

In conclusion, bias can have an indirect yet significant impact on even the most carefully executed risk assessment. Giving due consideration to these factors will reduce the probability of unintended or unseen bias, which will improve the quality of both the risk assessment itself and the decisions resulting from it, in turn directly enhancing the safety and health of our communities.

Watch Dr. Gina Vincent’s full presentation: Racist algorithms or systemic problems? Risk assessments and racial disparity.

Learn more about MHS’ Level of Service/Case Management Inventory (LS/CMI).